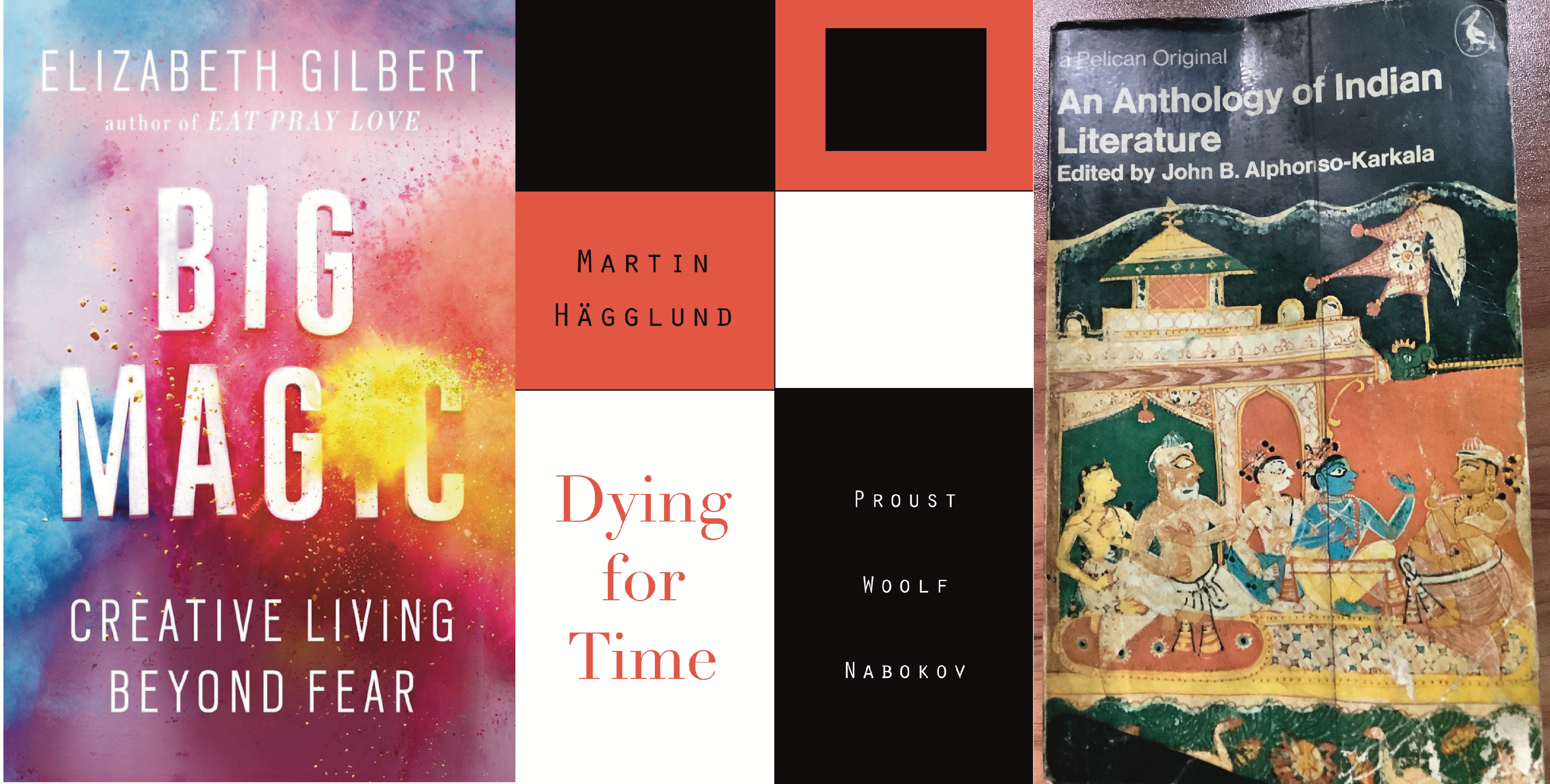

In the first chapter of her book Big Magic, Elizabeth Gilbert writes about courage. Her notion of ‘creative living’ is “living a life that is driven more strongly by curiosity than by fear.” There are plenty of reasonable and unreasonable things to fear, and it is exhausting, boring even, to indulge in them, ruminating over extended periods of time. I find myself agreeing with the premise, and decide to utilise fear toward constructive outcomes rather than giving in to the unproductive freeze response. I do not need a safe space, but I understand the need for building one that nurtures. Reading the book, I resolve to coexist with my fears and anxieties, and work with and through them.

I convince myself that I need to learn how to be brave. Or maybe, I need to cultivate more kindness toward myself and affirm that I am already brave. That bravery is not only in the more obvious ways that people are brave, but also in little things such as waking up to humble days of toil and even writing this sentence. In time, even my disenchantment can be repurposed into a fuel for creative living; there is hope yet.

We are all Dying for Time, Martin Hägglund writes in his literary criticism of the works of Proust, Woolf, and Nabokov.

The explicit memorization of the present (now remember) recurs with a remarkable frequency in Nabokov’s writings and is symptomatic of his “chronophobia,” a term that he himself introduces in Speak, Memory (17). The main symptom of chronophobia is an apprehension of the imminent risk of loss and a concomitant desire to imprint the memory of what happens. It follows that chronophobia—in spite of what Nabokov sometimes claims—does not stem from a metaphysical desire to escape “the prison of time” (Speak, Memory, 18). On the contrary, it is because one desires a temporal being (chronophilia) that one fears losing it (chronophobia). Without the chronophilic desire to hold on to the moment, there would be no chronophobic apprehension of the moment passing away. It is this chronolibidinal desire to keep temporal events that motivates Nabokov’s autobiographic protagonists. They seek to record time because they are hypersensitive to the threat of oblivion.

Martin Hägglund, Dying for Time (p. 82)

Without the inscription of memory nothing would survive, since nothing would remain from the passage of time. The passion for writing that is displayed by Nabokov and his protagonists is thus a passion for survival.

Martin Hägglund, Dying for Time (p. 84)

Writing is here not limited to the physical act of writing but is a figure for the chronolibidinal investment in living on that resists the negativity of time while being bound to it. Nabokov scholarship, however, is dominated by the thesis that his writing is driven by a desire to transcend the condition of time. The most influential proponent for this view is Brian Boyd, who in a number of books has argued that Nabokov aspires toward “the full freedom of timelessness, consciousness without the degradation of loss.” According to Boyd, the possibility of such a life beyond death is a pivotal concern in Nabokov’s oeuvre. Boyd is well aware that Nabokov and his protagonists are resolute chronophiles who treasure their memories and temporal lives. As he eloquently puts it, “the key to Nabokov is that he loved and enjoyed so much in life that it was extraordinarily painful for him to envisage losing all he held precious, a country, a language, a love, this instant, that sound.”

A small part of me regrets reading this book. I was not exactly out there looking for an existential crisis to have for dinner. But books never ask politely if they can change something within you and if you’re feeling up to being emotionally traumatised.

I am reminded today of how it came to be eleven years ago that I bought An Anthology of Indian Literature by John B. Alphonso-Karkala for €1 from a stand outside a bookshop near the LMU campus in Munich. The unhappy land had greeted me with “India is a fucked up place”, “You’d look more pretty if you smiled”, and “I doubt you can even handle doing a PhD, we’ll see” for more than six weeks. I was starving for something to read in English and distract myself. My flight back home later that weekend was in the evening and knowing that I had nowhere else to go after vacating the apartment, I had decided to spend almost all of that sunny day reading at the airport.

Not so much for its content perhaps, but this book is invaluable to me. I had spent the summer away from mangoes and the editor’s name reminded me of that sad fact. It had stories of my land, I was going back; I only meant to hold the book in my hands, but it felt like a warm embrace instead.

A couple of days ago I reread Karma, a short story by Khushwant Singh, included in the Anthology. When I had read the story all those years ago, I did not know that he wrote anything besides his weekly column ‘With malice toward one and all’ in the national daily. The sensibilities of one’s home invariably provide comfort in an inscrutable foreign land. One day I will make time to read his books as well.

Here I am today despairing at the yellowing pages and searching old bookshops around the city for a newer print or a digital version in vain, and someone decided that they did not need this book anymore and gave it away for a euro. Unbelievable.